Canzoniere 264

March 3, 2012 1 Comment

Presentation by Mike Hodder; Report by Jennifer Rushworth:

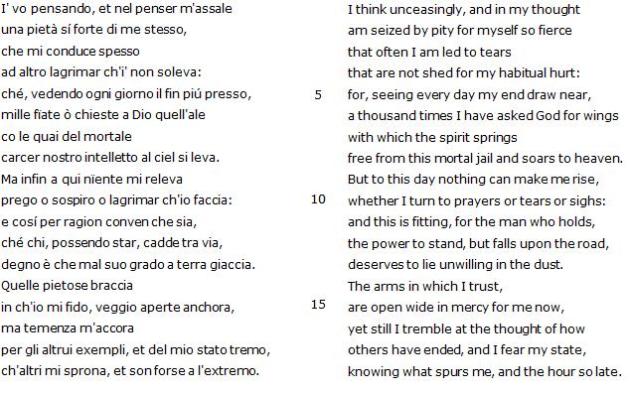

This canzone, Rvf 264, is called “the great canzone of inner debate” by Durling. It acts as a pillar of the Canzoniere, opening the In morte section. The fact that Laura is still alive at this point raises some interesting questions as to the criteria which govern the structure of the collection. The idea is that Petrarch’s penitential impulse is triggered not by an external event but is the result of an organic internal process which is never fully explained. The sense of a gradual build-up of momentum pervades the poem, particularly through the use of gerunds and temporal indicators signifying repetition.

The poem is thought to be a product of the late 1340s or early 1350s, composed around the same time as Petrarch was working on the Secretum. As such, it is no surprise that both works share similar concerns: the consequences for the poet’s soul of his desire for Laura on the one hand, and for literary immortality on the other.

It is an anniversary poem – the twenty first canzone in the Rvf, corresponding to the twenty first year of the poet’s love for Laura. Within the narrative of the collection, this places us in the year 1348 – the year of Laura’s death. If Rvf 3, that is the poem in which Petrarch first sees Laura on Good Friday, corresponds to 6 April, then Rvf 264 takes place on Christmas Day, the beginning of the new liturgical year. The symbolism is clear – if the Good Friday sonnet represents the start of the poet’s torments, the Christmas canzone is supposed to symbolise a re-birth, the beginning of a new consciousness and a new orientation away from the earthly passion for Laura and fame, towards God and the path to true immortality.

However, this forward (or upward) drive is continually undermined as the poet finds himself unable to detach himself from what Augustinus refers to as the two gilded fetters in Book III of the Secretum.

The first stanza recalls Rvf 1 almost immediately: “spero trovar pietà non che perdono”. The poet’s tears are of a different kind: he does not weep because of his amorous misfortunes, but rather in desperation of his salvation and his inability to find consolation no matter what he does (ll. 9-10)

The first person pronoun which opens the poem gives way to the characteristic Petrarchan psychomachia which we have observed in previous sessions. The poet’s thoughts converse with (or should that be lecture to) his mind and his heart. He becomes a passive observer. When the “io” returns midway through the fourth stanza, it is in the context of being ignored. This psychological rupture foreshadows the ultimate rupture: the separation of the soul from the body in l. 66.

The “io” is forcefully re-established from the fifth stanza until the end, appearing in the opening line of each stanza and the congedo: “Ma quell’altro voler di ch’i’ son pieno” (l. 73); “Quel ch’i’ fo veggio, et non m’inganna il vero” (l. 91); “Né so che spatio mi si desse il cielo” (l. 109); “Canzon, qui sono, ed ò ’l cor via più freddo” (l. 127).

Casting itself as a watershed poem, certain words and phrases at various points recall previous poems and anticipate others: the poem is littered with allusions to Rvf 1; Rvf 3 makes an appearance (l. 90), along with Rvf 90 (l. 45). The opening line anticipates l. 1 of 365 “I’ vo piangendo”; wings which carry the poet towards heaven appear in 339 and 362; ll. 71-2 recall the final tercet of 269. His forward drive is continually undermined as he is pulled backwards by the chains binding him to earthly pleasures: vergogna e duol che ’ndietro mi rivolve (l. 123). Petrarch finds himself stuck in a sort of limbo, experiencing his ultimate psychological nightmare – the loss of control. He is presented as passive: waiting for help. He is terrified by his insignificance: mirando ’l ciel che ti si volve intorno / immortal et addorno (l. 49-50).

There is an oscillation between centrality of the “io” and its insignificance throughout the poem. There is also an opposition between movement and stasis. This movement is, however, illusory, as although it appears to be going forward it amounts to running on the spot. This is movement without progression or evolution, a movement that is self-perpetuating and based on habit.

One important intertext is St. Augustine, Confessions (Book VIII), for the appearance of the theme of ‘consuetudo’, habit: “The enemy held my will, and out of it he made a chain and bound me. Because my will was perverse it changed to lust, and lust yielded to habit, and habit not resisted became necessity.” Likewise, in book VIII: “the law of sin is the fierce force of habit, by which the mind is drawn and held even against its will, and yet deservedly because it had fallen wilfully into the habit.”

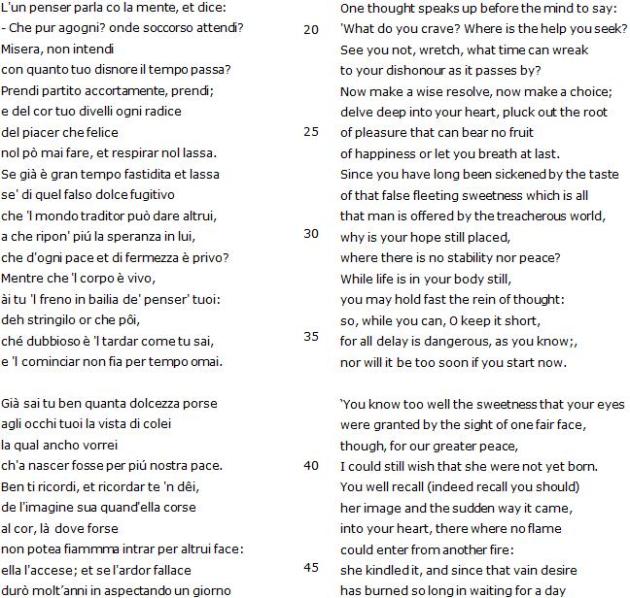

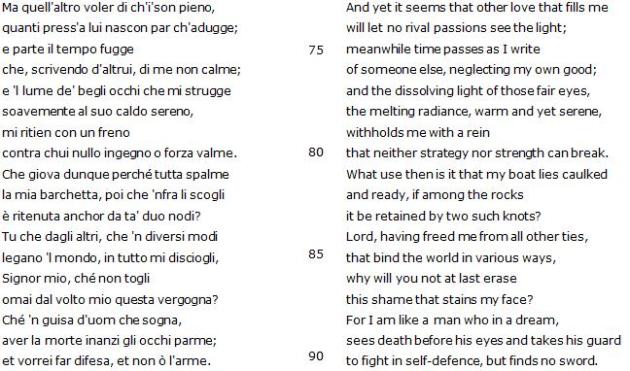

The themes of stanza one are self-pity, the desire of the poet to raise his intellect towards God, and his fear and anticipation of his own death. In stanza two, a ‘penser’ (thought) addresses the poet’s mind, scolding him for his lethargy and encouraging him to take control of himself before it is too late. In stanza three, the memory of Laura dominates, as signified by the proliferation of ‘or’ senhals (13 occurrences over the course of 18 lines). In stanza four, the poet asserts the vanity of literary ambition. In stanza five, the poet recognises his inability to escape his love for Laura, which he counters by appealing to God for help as he acknowledging his own helplessness. Stanza six acknowledges the idolatrous nature of his desire for Laura but recognises that emotions are stronger than reason. Stanza seven asserts the uncertainty of human existence and, on a personal level, visible signs of his advancing age. The incipit is repeated in ‘vo ripensando’ (v.120). In the congedo, the poet expresses once more his fear of death, and reaffirms his desire for change. Yet the final line with its stark antithesis is painfully resigned and the poet’s inner conflict is left unresolved.

Discussion:

This poem reminds us that the in morte section refers not only to Laura’s death, but to the poet’s anticipation of his own death. It is probably to be read in conjunction with sonnet 150, which is again an inner dialogue (between the poet and his soul – ‘Che fai,alma? che pensi?’).

The canzone is highly symmetrical, structured around sets of dichotomies and conflicting thoughts. A further contrast is that between self and Other: this is a song of alterity, of alienation, of not being oneself, almost a manifesto of a lack of self-identification, hence the omnipresence of ‘altro’, ‘altra’, ‘altrui’ in this poem. It is telling that ‘altra’ and ‘alma’ are linked by assonance, and also are possible senhals of Laura (a, l, a).

Reading the poem in the context of Christmas Day is productive, as it highlights the presence of many references to birth. Laura ends up being an anti-Christ, in fact, if we read line 107 in opposition to the Christological model (Laura is ‘quella che sol per farmi morir nacque’, whereas Christ is born to bring new life). Instead, the poet seems almost Christ-like, given lines 110-111 (‘novellamente io venni in terra / a soffrir l’aspra guerra’). Moreover, ‘la man destra’ (121) is a further Christological allusion (Christ sits on God’s right hand), while ‘l’un lato punge’ (the left-hand side) is perhaps an oblique reference to Christ being pierced on the Cross on his left side.

In terms of Petrarch’s relation to Dante, this poem presents further contrasts. While Dante’s model of poetry was under the dictation of love (‘I’vo significando’), Petrarch’s model is Cavalcantian, destructive, circular, repetitive and self-fragmenting: ‘I’vo pensando’. Petrarch sees death as an escape (perhaps because he is too worried about hell on Earth, in this life, to be worried about the Afterlife), whereas Dante has already shown that Hell is a repetition of sinful, wrong obsession, i.e., not an escape. Petrarch’s desire for death, and possibly even suicidal tendencies, were raised in relation to line 126 (‘a patteggiar n’ardisce co la morte’). Dante has a successful, productive relationship with the Other (Beatrice and God, ‘com’altrui piacque’), whereas Petrarch is stuck in self-absorption and in love with an individual whose own suggested narcissism is worrying (v.108, ‘a me troppo, et a se stessa, piacque’ – compare RVF 126 for Laura’s narcissism).

There are consistent references to Purgatorio in this poem (for instance, the ‘barchetta’ which recalls Purg. II, or the ‘nodi’ that recall Purg. XXIV). Lines 68-69 (‘ma se ’l latino e ’l greco / parlan di me dopo la morte, è un vento’) recall Purg. IX, lines 100-101: ‘Non è il mondan romore altro che un fiato / di vento’. It was noted that the ‘ma’ at the start of line 68 is illogical, seeming to oppose itself to an implied but unexpressed and telling thought or desire. It was also discussed that ‘vento’ is always negative in Petrarch (it does not have overtones of inspiration or the Holy Spirit here).

The poem calls into question the usefulness of language, in a similar way to RVF I: lines 9-10 (‘Ma infin a qui nïente mi releva / prego o sospiro o lagrimar ch’io faccia’) implicitly render part one of the Canzoniere useless (in salvific terms, although of course not in aesthetic terms). The final line of the poem was discussed in terms of its Ovidian and Pauline undertones (Ovid, Metamorphoses, VII, 20-21; Paul’s letter to the Romans 7:19). However, it was agreed that whereas in Dante you have to know the subtext in order to understand the new text, in Petrarch this is often not the case. Rather, Petrarch tends to hide or obliterate his sources in his writing process.

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if

you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.